Bumi PLC: Corporate Governance Concerns Give Investors “Coal” Feet

The global commodity boom in late 2000 led to rising commodity prices, and companies mining minerals and resources saw their share prices surge as investors poured money into these markets. Indonesia benefitted from these hot money flows; however, those who invested in coal producer Bumi PLC in 2011 could not have envisioned the corporate governance concerns that would besiege the company just one year later.

The case underscores what’s at stake for investors and the need for effective reforms to address corporate-governance issues and conflicts at the boardroom level that ultimately affect shareowner value.

How It All Unraveled

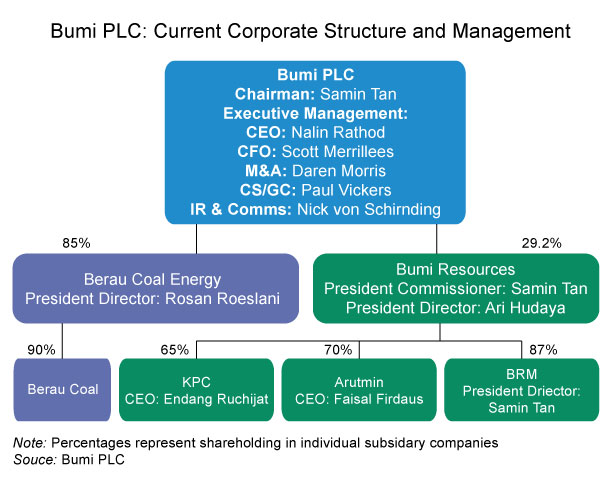

In November 2011, Vallar — a London-listed cash shell company owned by financier Nathaniel Rothschild, a 41-year-old scion of the prominent Rothschild family, and James Campbell — engineered a reverse takeover of Indonesian coal assets with a combined value of about US$3 billion. Bumi Resources (owned by the Bakrie family) and Berau Coal Energy (a smaller rival in Indonesia owned by Rosan Roeslani) were injected into Vallar, leading to Vallar owning a 75% stake in Berau and a 25% interest in Bumi PLC. In June 2011, Vallar was renamed Bumi PLC and obtained a premium listing on the London Stock Exchange. Bumi Resources is Asia’s biggest exporter of thermal coal and the flagship company of the influential Indonesian Bakrie family. As a result of the reverse takeover, the Bakries own 47.6% of Bumi PLC, Rosan Roeslani owns 13.11%, and Nat Rothschild’s share is diluted to 11.9%.

The stock was trading on the London Stock Exchange at £11 in July 2011. It slumped to £1.61 as of 4 October 2012 before recovering to about £2.40. What led to the big fall in share price and some Bumi PLC investors losing about 75% in value?

The catalyst was the commodity slump and falling coal prices in October 2011, which led to a fall in Bumi PLC’s share price. This triggered a margin call of Bumi PLC shares owned by the Bakries, which were pledged to Credit Suisse for US$1.34billion for loans to the Bakries. To remedy the situation on 30 December 2011, the Bakries sold half of their stake to Samin Tan of PT Borneo, another Indonesia-listed coal company. The Bakrie Group and PT Borneo then jointly owned a 47.6% stake in Bumi PLC.

The falling coal prices would eventually impact the credit rating and balance sheet of Bumi Resources, which was saddled with debts of about US$3.9 billion, including US$1.5 billion owed to sovereign wealth fund China Investment Corp.

By early 2012 news broke that there was an internal conflict between the Bakries and Nat Rothschild, which intensified when the latter called for a “radical cleanup” in Feb 2012. Indeed, Rothschild sent a letter to the Bakries calling on them to improve the corporate governance of Bumi Resources and to call back loans to related companies. When the letter was leaked, it angered the Bakries. At the annual general meeting (AGM) of Bumi in March 2012, Rothschild was ousted as co-chairman by the Bakries, and Samin Tan was appointed chairman. Rothschild remained on the board as a non-executive director. On 24 September 2012, Rothschild commissioned a London law firm to investigate potential financial irregularities of US$637 million (£371m) in the books of Bumi Resources classified as “development funds and exploration assets,” including costs associated with exploration of oil and gas in Yemen, where operations were suspended due to the unstable political situation. PriceWaterhouseCoopers, the statutory auditor of Bumi PLC, had earlier highlighted the difficulties of determining the value of these exploration assets in its audit review.

How Have Regulators in Indonesia and London Responded?

The Indonesian Stock Exchange requested that Bumi Resources and PT Berau clarify issues surrounding the independent investigation by their parent company, Bumi PLC, into irregularities in the placement of development funds and assets by two of Indonesia’s biggest coal producers.

Meanwhile the Financial Services Authority (FSA) issued a consultation paper in October 2012 to enhance effectiveness of the listing regime and improve governance and minority protection in premium listings where there is a controlling shareholder, as with Bumi PLC. Under the proposed rules, the British regulator would require a majority of independent directors on the board where a controlling shareholder exists (defined as 30% ownership). Alternatively they will need to have an independent chairman to serve on the board, along with 50% independent directors. This reflects current rules in India.

Secondly, the FSA plans to introduce a new dual-voting requirement for election of independent directors for premium-listed companies. Under this arrangement, all independent directors would be approved by all shareholders and supplemented by an approval by only independent shareholders. If there is a conflict between the two results, there would be a 90-day period in which the independent directors would be elected again by a simple majority. The rationale for this is to provide a mechanism for minority (independent) shareholders to exert some influence in the election process.

Another important proposal is mandating a relationship agreement between the controlling shareholder and the company to ensure that control is not abused, in particular through related-party transactions. Shareholder relationship agreements are also used to govern the rights of parties to nominate directors and appoint key management positions where a company has a few strategic investors with substantial holdings. In the case of Bumi PLC, a shareholder relationship agreement was entered into on 16 June 2011 that gave the Bakries the right to nominate up to three directors, and to hold the positions of chairman, chief executive officer, and chief financial officer, respectively. Additionally, PT Bukit Mutiara (controlling shareholder of coal producer Berau Coal) can nominate one non-executive director, provided they each retain a minimum of 15% of voting rights at an annual general meeting.

Are the New Rules Adequate?

The FSA philosophy is based on the principles of disclosure, and requiring “comply and explain” for non-compliance. While the changes would lead to some improvements, investors should learn some valuable lessons from the Bumi PLC saga. For starters, it is not sufficient to just tighten the rules of the company listed in London. In a holding company structure such as Bumi PLC, investors should look further into the subsidiaries (Bumi Resources and Berau Coal) and their governance; where the assets, operations, and management are located can make a significant difference. Take related-party transactions as an example. At the holding company level, you can only improve disclosures. Effective regulation of related-party transactions requires independent shareholder approval of recurring items and large transactions at the subsidiary level. In this case investors should examine carefully the practices of Bumi Resources and Berau Coal and whether there is sufficient investor protection in the listing rules of the Indonesia Stock Exchange.

In the May 2012 AGM proxy materials, the resolution to elect all of the directors of Bumi Resources was a bundled resolution, or one slate for all the directors to be elected. No information was given on the biographies of the directors and whether any of them had relationships with the controlling shareholders. This is not consistent with international corporate governance standards and best practices.

The trigger point that led to the downfall of Bumi PLC was not the widely reported boardroom tussle. It was the fall in share price that triggered the redemption of shares pledged for loans to the Bakries. It is a common practice for Asian entrepreneurs to pledge their shares for loans and credit facilities, and share-pledge disclosure requirements vary significantly across markets. There have been a number of instances in the past few years in Asia where ownership of companies has changed hands as a result of this, most notably Satyam Computers in 2009.

The Bakries and many tycoons in Asia have very close relationships with political leaders over a long history that dates back to the time right after World War II. Through their influence the tycoons have benefitted by having monopolies over key assets such as mineral resources, timber concessions, and exclusive licenses to operate casinos and toll roads. Therefore, while an international investor may see hidden value investing in a coal asset such as Bumi Resources, unlocking value by improving corporate governance and management would first require an understanding of the culture, history of management, and governance practices of the local partner. Until trust and friendship is won, changes are unlikely to occur.

In the latest turn of events, the Bakries announced a proposal to buy back Bumi Resources for US$1.2billion in cash. The price of Bumi has been trading around US$2.40 in mid-October following the announcement. Nat Rothschild resigned as a director of Bumi PLC on 15 October. Indonesia and Southeast Asia have just entered the monsoon season. Dark clouds and a soggy coal market may leave investors with cold feet for a while until the skies clear.

If you liked this post, consider subscribing to Market Integrity Insights.

Photo credit: ©iStockphoto.com/titop81

Updated 26 October 2012 to correct editing error in second to last paragraph.

Many investors look at emerging names as undervalued and a platform for shareholder activism, improving corporate governance etc, however the truth is these shareholders are based in countries others than the listing or the incorporation country of the company hence many a times these investors are far from reality in terms of what can be achieved vs. what is sold to them as a story of growth

Bihari – Not sure if your assertion that “these shareholders are based in countries others than the listing or the incorporation country of the company hence many a times these investors are far from reality in terms of what can be achieved vs. what is sold to them as a story of growth” explains these fiascos.

There are plenty of local institutional investors in India who have been taken for a ride in stocks like Satyam Computers or pick a stock in the the real estate sector, et cetera.

Venkatesh