HFT Cause and Effect: What Is the Role of Exchange Industry Economics?

The publicity frenzy over high-frequency trading (HFT) in the wake of the Michael Lewis book Flash Boys has led to much conjecture, claim and counter-claim over how the current market structure serves investors. But what’s been missing from the debate is a deeper analysis of the economics behind the exchange industry. It’s an unusual mix of something close to what economists call perfect competition (the epitome of a free market) and price controls (the antithesis of a free market). Understanding these forces is the key to unlocking the cause and effect of HFT.

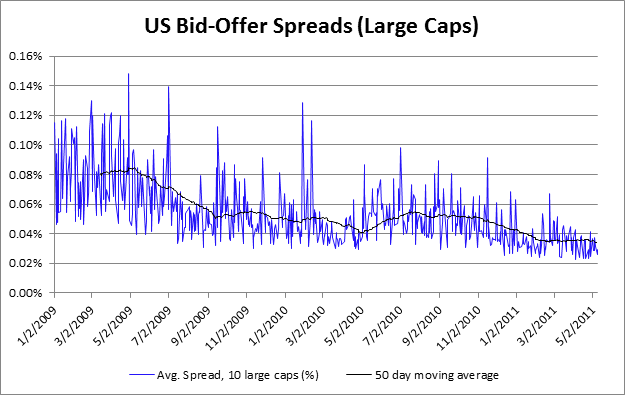

First, let’s look at the perfect competition aspect. The exchange industry is characterised by a large number of trading venues each competing for business in the same “product” — namely, the trading of listed stocks. The same common stocks can be traded across all 13 US exchanges and the many more dark pools and alternative trading systems that exist in the marketplace. Competition among a large number of firms providing near-identical products (i.e., trading of the same stocks) is the very essence of perfect competition. And as with any perfectly competitive market, the result of competition is a reduction in the cost of the product. In the exchange world, we see this via the approximate 50% reduction in bid-offer spreads — a measure of the cost of trading — in recent years (see chart).

Source: Based on data from FactSet

What brought about this competitive marketplace? In short, regulation. Starting around 2005–07, Regulation National Market System (NMS) in the US and the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) in Europe removed certain protections that enabled the incumbent exchanges — the likes of the NYSE or the national stock exchanges in Europe — to maintain near monopolies in share trading. A proliferation of competing exchanges and alternative trading venues ensued, fragmenting trading volume and liquidity across disparate venues. Fragmentation is therefore the by-product of competition, itself the intended result of regulation.

Fragmentation (which we can equate to competition) can be considered a positive outcome. Studies bear this out; the 2009 paper on market microstructure from CFA Institute found a benign effect between fragmentation and the cost of trading measured by bid-offer spreads. A more comprehensive analysis on fragmentation is this SEC literature review, which cites beneficial effects from fragmentation among lit markets.

So far, so good.

The second force affecting exchange economics is a form of price controls. Specifically, Reg. NMS caps the access fee for “taking” liquidity — hitting resting limit orders on exchanges — at US$0.003 per share. The intent of this rule is to limit the direct cost of trading on exchanges and ensure that public markets are accessible to all investors wishing to trade there. But coupled with the fragmentation, there is perhaps an unintended effect of this regulation as well — namely, more fragmentation.

At this point, a digression is needed. In the middle of the last decade (and in some instances earlier), the exchange industry demutualised. The switch to a for-profit business model coincided with adoption of the maker-taker fee system, whereby liquidity suppliers (makers) receive a rebate for posting resting orders and liquidity demanders (takers) pay a fee for hitting those orders. Net revenue is thus the difference between the take fee received and the make fee paid out. Exchange operators competed on the rebates offered to attract traders to their platforms — a tactic that enabled new trading venues to secure volume and (successfully) take business away from the incumbent exchanges.

If maker fees were a form of price competition (or inducement) that facilitated fragmentation, taker fees were a form of price control that, perversely, also fuelled fragmentation. With competition eroding market shares and asymmetric price controls compressing margins, revenue collection — essential in the demutualised world — became dependent on scale. One way to grow scale was to create more exchanges — and hence more fragmentation.

Witness, for example, the operation of two separate exchanges (and separate pricing schedules) by BATS and Direct Edge. BATS operates BATS Z exchange and BATS Y exchange, which have about 8% and 3% market shares, respectively, while Direct Edge operates EDGX exchange and EDGA exchange, with about 7% and 3% market shares, respectively.

So, with a regulatory-mandated cap on prices, revenue from access fees becomes a function of the volume of fees collected. The exchange industry thus became dependent on scale and volume. How to increase exchange volume? Enter HFT.

There are of course a number of factors behind the adoption and expansion of HFT; for the most part, it is a natural technological evolution in trading markets perennially dependent on speed and the search for competitive advantage. But the role of exchanges as enablers of this phenomenon — driven by the need to grow volume amid a competitive, fragmented marketplace with price controls — should not be overlooked.

HFT can be viewed in one sense as a means to pump more transactions through the system. Consider the regular hours of trading in the US (9:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m). That’s six and a half hours, or 390 minutes, or 23,400 seconds, or 23,400,000,000 microseconds. With transactions completed in a matter of microseconds (or even shorter), it’s easy to see that a lot of volume can be generated in more than 23 billion microseconds — hence its attractiveness from exchanges’ perspective. And with some HFT firms having ownership stakes in the exchanges, it’s no surprise that there is a strong alliance between exchange operators and HFT firms.

Another potential restriction on exchange revenue lies in the form of the rules governing the collection, consolidation and distribution of market data. Under Regulation NMS, exchanges are subject to revenue-sharing arrangements in relation to the provision of data to the consolidated quote and tape systems. But the same rules also permit exchanges to distribute their own data independently.

Again, given the fragmentation, the for-profit motive of exchanges, price controls, and the incentive to fuel HFT (a tactic to grow volume), exchanges developed business lines around market data. The development of proprietary data feeds and other related services like co-location facilities enabled exchanges to diversify revenue streams (necessary given their loss of market share) and, at the same time, facilitate HFT.

Exchanges are required to send trade information to the central data consolidator at the same time they disseminate information on their proprietary data feeds. But because of aggregation, information published on the consolidated quote and tape is visible approximately five milliseconds later than proprietary exchange feeds. These data feeds are thus a critical source of advantage for HFT firms.

Is it right to create market data “products” in this way, and does it create the opportunity for unfair advantages? One could argue that the intellectual property of the data — the quotes and transaction information — belongs to market participants supplying bids and offers and trading on exchange systems. On the other hand, one might argue that the existence of an exchange is necessary for the formation of prices, and it this centralised structure (the exchange platform) that “creates” the prices. Either way, market data is now a significant source of revenue for exchanges. As a business line, it is subject to differentiated pricing, much like in other industries. If you want the fastest, most granular data, you can pay top dollar — if you are happy to receive data on a delayed basis, you can get it for free after 15 minutes. In most industries, such price discrimination is common and accepted — you get what you pay for (think of the airline industry for example) — but as with other things in the exchange world, price discrimination surrounding market data is not a black-and-white issue. Whether it is “fair” perhaps depends on one’s view over the rights and ownership of market data.

Finally, another factor that sits alongside HFT and fragmentation is the growth of dark trading. Broker–dealer internalization networks that siphon off retail order flow and the payment for order flow arrangements that facilitate this business model are a significant factor in the current market structure. We have commented on the issues associated with internalization and dark pools elsewhere — suffice to say that disentangling cause and effect with regard to these and the other issues presented here is difficult and subject to feedback loops.

In conclusion, regulation has played a significant role in creating the current market structure, both with intended and unintended consequences. The ensuing confluence of fragmentation, exchange demutualisation, and the maker–taker fee system feed into more fragmentation, the need for scale and HFT, and market data innovations. In essence, the market structure reflects a complex web of related factors. Disentangling this web is no easy task; perhaps the best place to start is the maker–taker pricing system and payment for order flow arrangements. Regulators would do well to focus on these issues rather than attempt wholesale market structure reforms.

If you liked this post, consider subscribing to Market Integrity Insights.

Photo credit: @iStockphoto.com/Nikada