European Union Revisits Securitization Rules to Bolster Capital Markets

As the European Union grapples with sluggish economic growth and intensifying capital demands from the climate and digital transitions, policymakers are turning to underused financial tools to unlock private investment. Chief among them is securitization—a market that’s been lackluster since the global financial crisis (GFC).

This week, the EU Commission (the European Union’s executive) kicked off this process with a significant revision of regulations governing securitizations. For investment professionals, the reforms signal a potential shift in the role securitized assets can play in portfolios, balance sheet management, and broader capital markets integration.

The proposals were of course welcomed by Europe’s banks, which are already dominant in the EU financial system. But there could also be important benefits for the European Union’s capital markets agenda. Pooling loans with similar origin, such as residential mortgages, creates portfolios that match specific investor mandates and risk tolerance. For instance, securitizations of non-performing loans (NPLs) are estimated to have removed more than EUR 200 billion from EU banks’ balance sheets and, on the back of government guarantees, allowed specialist investors to take on restructuring and resolution.

There could also be important benefits for the European Union’s capital markets agenda. Pooling loans with similar origin, such as residential mortgages, creates portfolios that match specific investor mandates and risk tolerance. For instance, securitizations of non-performing loans (NPLs) are estimated to have removed more than EUR 200 billion from EU banks’ balance sheets and, on the back of government guarantees, allowed specialist investors to take on restructuring and resolution.

A Tale of Two Markets: European Union vs. United States

A comparison between the size of the EU and US securitization markets is particularly striking and has motivated many calls for a reform in Europe.

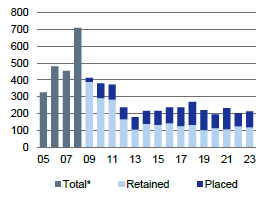

Ahead of the financial crisis European securitization boomed, just as it did in the United States, peaking at EUR 711 billion in issuance in 2008. Annual issuance volumes then contracted sharply and have barely recovered since then. Recent transactions averaged around EUR 200 billion annually. By comparison, the United States staged a much more rapid rebound in line with the recovery in the housing market, with the active support of the government sponsored agencies guaranteeing more than 80% of mortgage-backed securities.

Last year, US annual issuance amounted to 4% of GDP, roughly 10 times larger than the equivalent amount in the European Union. The very different structure of EU financial markets explains a good part of this difference. Covered bonds, which collateralize issues with specific asset pools, are a long-standing refinancing tool for EU banks. Given how insolvency and other commercial laws differ across EU states, few asset types can be easily bundled for a transfer to non-bank investors. Crucially, the European Union lacks public securitization platforms, such as the US government-sponsored entities, which could bundle and guarantee bank placements in the market.

Chart 1. European (incl. UK) true-sale securitization volumes, EUR bn.

Source: Deutsche Bank, based on AFME.

Fragmented Markets, Missed Opportunities

The penetration of securitizations in the EU capital market is even more limited than these figures would suggest. European banks typically retain half of the true-sale securitizations, using the senior tranches for liquidity management purposes and central bank refinancing. Moreover, EU banks often invest in each other’s securities while onerous due diligence requirements have discouraged investments by pension funds and other institutional investors.

As in other capital market instruments, the use of securitizations for bank refinancing is highly uneven, with outstanding volumes of more than 10% of GDP in the Netherlands, and less than 2% of GDP in Germany, with several countries not participating in the market at all. Both supply by issuing banks, and the investor base are highly concentrated in a small number of players. Traditional asset types like residential mortgages underpin most issues, while the use of other asset types such as renewable energy or digital infrastructure loans has been miniscule. Oddly, and perhaps as a reflection of restrictive rules, synthetic securitizations, which transfer credit risks but not the underlying assets, have grown strongly. The European Union is a global leader in synthetic securitizations.

Rules that Bit Too Hard

Some key lessons were learned the hard way during the GFC. Securitizations remove risks from banks’ balance sheets and inherently suffer from so-called moral hazard. Because banks and other originators expect to sell loans, they become sloppy, and investors pay the price. A large part of the problem in the financial crisis was indeed due to weak screening and monitoring efforts by lenders.

Initially, reforms sparked by the GFC were well aligned among G20 governments. They imposed requirements on originators to retain ‘skin in the game’ and banned some complex products. Most major jurisdictions introduced stricter disclosure around due diligence and imposed higher standards for capital adequacy and the use of securitized assets in liquidity buffers. Securitized assets were no longer treated as equivalent to underlying assets, due to added structural risks such as tranche-level credit rating uncertainty.

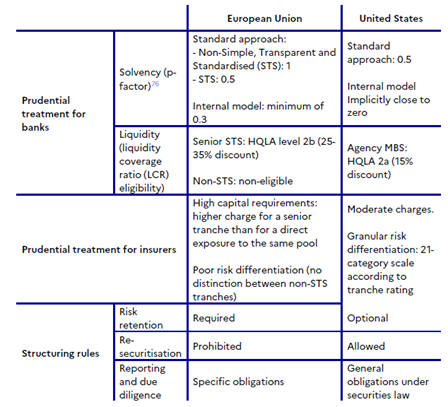

In 2019, the European Union adopted a new Securitisation Regulation that fleshed out these principles of risk-retention and transparency and also banned re-securitization. Prudential treatment of exposures by banks and insurers was relatively strict, though minor concessions were made for securitizations that reflected the higher standard of being deemed simple, transparent, and standardized (STS).

Many European regulators saw this treatment as justified by crisis-era defaults, despite most involving complex products. The Basel III framework for bank regulation also resulted in a relatively restrictive treatment in banks’ internal capital adequacy models. Table 1 underlines how EU treatment to date has been more restrictive than that in the United States.

Table 1. Comparison of aspects of the regulatory and prudential framework for EU and US securitization.

Source: Banque de France, C. Noyer (2024).

The Regulatory Reset: What’s on the Table

As the initiator of EU rules, the European Commission now accepts that the regulation adopted in the aftermath of the GFC was too complex and imposed unnecessarily high regulatory costs. One example is the capital buffers banks must hold when investing in securitized assets. Analysis by rating agencies also suggests that recent default rates are in fact little different from those of the underlying assets. This is yet to be tested in a significant credit cycle, however.

A broader problem is that the body of EU financial rules has become extremely complex with much additional detail added by national supervisors. Similarly, the three laws governing securitization — covering banks, insurers, and structuring — often duplicate one another.

The European Union is proposing cutting some red-tape and easing the risk treatment of securitizations for banks and insurers. Measures under consideration include:

- Reducing reporting requirements: This appears uncontroversial. Though originally intended to enhance transparency and investor due diligence, the operational costs have proven excessive. These securitization-specific rules go well beyond typical issuer or investor standards, and large banks and repeat issuers are already well known in the market.

- Adjusting capital requirements for bank investors: While a modest premium is warranted, capital weights averaging twice those of the underlying assets no longer align with actual default data. Another goal is to make these assets more attractive for meeting liquidity requirements, while explicitly maintaining compliance with the Basel III framework.

- More complex securitizations: Securitizations not meeting the EU standard of being simple and transparent could be made more attractive for insurance fund investors.

Not Just Reform: Integration Would Transform Markets

But tweaks to transparency provisions and capital weights only go so far. Europe’s fragmented banking market and diverging national standards that affect asset quality have prevented the emergence of large homogeneous asset pools. National provisions for ownership transfer and insolvency work very differently across EU states. Even though the European Union has an elaborate framework for classifying sustainable activities and financial instruments, it has failed to develop green securitization on a larger scale.

In the United States, the two principal mortgage agencies have developed standards that define a nation-wide market for housing loans. Nothing comparable exists in the European Union as the role of the European Investment Bank (EIB) in this area is limited.

A public guarantee for certain types of securitizations would make such a platform particularly effective. This was a key proposal in a recent high-level report on the European Union’s capital markets union. Guarantees could be justified, especially where policy risks limit investor appetite for certain asset types, such as green mortgages or renewable energy. As in other areas, Europe’s financial market suffers from the lack of a common fiscal policy and institutions that could shoulder such risks.