Investing for Income: Can Currency Carry Trades Replace Evaporating Yields?

The collapse of interest rates to record lows in the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, Switzerland, and Japan has inflicted pain on those who rely on interest income.

“Financial repression” is the watchword for this phenomenon, coined by those who perceive governments to be misappropriating returns from savers. But near-zero interest rates may be a double-edged sword for income seekers. That is, although the low interest rates have dramatically curtailed interest income, they have made it cheaper to borrow for funding purchases of higher-yielding assets, or “carry trading.”

The search for income is luring investors into all kinds of carry trades, including yield curve bets, real estate investment trusts, high-dividend stocks, corporate credit, asset-backed securities, structured products, option-writing strategies, and more exotic vehicles related to insurance or longevity risk.

All of these strategies entail their own risks, and so too does the currency carry trade. The type and amount of risk and potential reward involved in currency carry trades can vary a lot, depending on how you play them and whether you use leverage.

Single-Digit Yields, Absent Borrowing

So, what kind of yield spread could a carry trade provide, as long as the higher yielders do not fall in value against the lower yielders? Right now, the top three coupon cows in the G–10 are the Norwegian krone, New Zealand dollar, and Australian dollar, with short-term interest rates around 1.5%, 2.5%, and 3%, respectively.

The meanest yielders include the U.S. dollar, pound sterling, euro, Swiss franc, and Japanese yen, with rates somewhere between 0% and 0.5%. Using the lowest yielder, the yen, to fund purchases of the Australian dollar could generate a 3% annual yield spread, without leverage and before the expenses of any investment fund used to put on the trade.

That’s more than the interest income on longer-term Treasury bonds, which could be vulnerable to rises in U.S. interest rates: A 2% rise in rates would knock approximately 15% off the value of a 10-year Treasury now paying near 1.6% and around 30% off a 30-year Treasury offering 2.75% interest. Currency carry trades using one- to three-month instruments have minimal interest rate risk, but they do have exchange rate risk.

Exchange Rate Risk

A simple way to gauge currency risk is to use a historical stress test: Just look at the worst past losses — for example, using a website such as dailyfx.com. From its highest to its lowest point, the Australian dollar dropped about 30% against the yen in late 2008. Over a 10-year time frame, an Australian dollar/yen carry trade could still have made 50% or more, mainly because the interest difference, in effect, lets you buy the higher yielder at a future or forward discount.

To ramp up the returns, how much leverage or borrowing would you want to apply to that carry trade?

A steady position with more than 3× leverage in this currency pair could have toasted just about all of your capital in 2008. (In practice, it’s almost certain that a margin call would have forced you to downsize the position before it hit zero.) Looking at potential rewards, anything less than 3× leverage would leave your yield spread in single-digit territory, at current yield spreads.

Developed Market Carry Trades

Investors who want to avoid perceived risks in emerging markets might restrict themselves to so-called G–10 currencies (U.S. dollar, Canadian dollar, Japanese yen, Australian dollar, New Zealand dollar, British pound, euro, Swiss franc, Swedish krona, and Norwegian krone), believed to be the world’s most liquid.

If investors also want to mitigate bank counterparty risk, they could execute this type of trade through the currency futures that have been traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) since 1972 (or buy a fund that does so).

Trading on exchanges does not completely eliminate the counterparty risk of trading with an individual bank or broker, but it does widely disperse this risk among the members that effectively co-insure the exchange. Hence, many investors believe that failures of exchanges and clearing-houses have been less frequent than those of banks and brokers — witness recent failures of Peregrine and MF Global.

Higher Emerging Market Yields

Even with the risks, some investors prefer to explore emerging market currencies, where interest rates can be higher than for the G–10. Although Brazilian interest rates have dropped to a record low, at 7.25%, they remain more than twice as high as the highest in the G–10; rates were as much as 12% last year. Indian interest rates are currently 8% and have ranged between 4% and 14% since the year 2000.

Argentinian interest rates, at more than 20% annually for three-month forwards, may be some of the highest in the emerging markets, but there may be special reasons for this, as explored in a recent posting.

A basket of emerging currencies could easily provide two or three times the yield spread of a G–10 currency carry trade, without leverage. To put these yields into perspective, we could make comparisons with corporate credit, where you would probably need to be comfortable with something close to a BBB credit, just below investment grade, for a 6% yield.

Such high-yield bonds have historically faced some risk of company default. This year, high-yield corporate defaults are running at around 3% of the universe of bonds, although holders of defaulted bonds may recover some value.

Credit risk in currencies can involve country default leading to depreciation, or the default can be the bank you are trading the currency with. The yield on emerging currencies can also be seen as partly a reward for the risk of country default, which has often been one event associated with currency collapses. However, the relationship between default risks and interest rates is not one-for-one.

Recently, for instance, the cost of insuring Argentinian sovereign debt against default dropped by 80% for certain maturities after a New York court decision. The three-month forward rate hardly moved in response. One explanation is that forward rates can be more closely linked to interbank rates, the rates banks pay to borrow from and lend to each other, than to government-set interest rates.

A growing number of emerging currencies can be traded as futures, including the Brazilian real, Czech crown, Hungarian forint, Mexican peso, Polish zloty, Chinese renminbi, Russian ruble, and South African rand (see here for the current list). Because not all emerging currencies are available as futures, some of these carry trades will involve a degree of bank counterparty risk (although this exposure and risk can be mitigated in many ways). As with corporate credit risk, defaults can cause losses, which may be partly recovered in time, as Lehman Brothers creditors are now seeing.

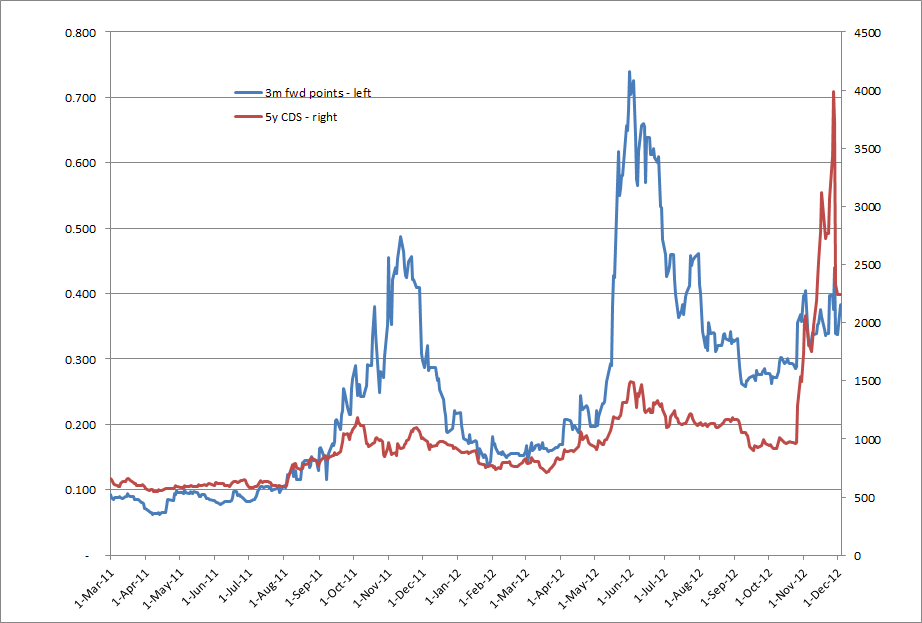

The chart below, provided by Rudolph Shally of Istar, a fund seeded by my employer IMQubator, shows that the five-year CDS (credit default swap) spread on Argentinian government debt has only a 50% correlation with the forward interest rates. So, country default risk is only part of the story.

Convertibility Risks

Depreciation is not the only risk of emerging currencies. When and if governments restrict convertibility, it can become difficult or impossible to trade them.

This was reported to have happened with the Malaysian ringgit some years ago. Remedies for such difficulties depend on the two-way agreements a fund or investor has with the bank or broker offering the forward contract. In the case of Malaysia, some patience was needed before the currency became easily tradable once again.

Are Emerging Market Risks Rising or Falling?

The general trend is clearly toward easier and more active trading in emerging market currencies as their growing economies increase cross-border trade. The bulls also argue that many emerging countries now have stronger balance sheets than developed countries, as measured by either government or private sector debt.

A hundred-year look into the past throws up hundreds of cases of emerging country defaults, but over the past 10 years, they have been much rarer: Argentina, Ecuador, and the Seychelles are the usual examples cited.

These fundamental stories may help explain why, since the late 1990s, emerging currencies have, on average, been appreciating against developed currencies, offering the long-term investor another layer of profit on top of the yield spread. Those who believe that some emerging currencies are undervalued may see potential for further appreciation, but this is far from assured because currencies need not move in tandem with valuations.

It is also true that some of the world’s most overvalued currencies, such as the Swiss franc and Norwegian krone, have continued to rise in value, possibly because investors seek them out as a “safe haven” or because of momentum players riding the trend. Investors need to decide if the yield spread from emerging currencies is enough to cover any volatility over their expected holding period.

Further Research

A list of exchange-traded currency instruments (both ETFs and ETNs ) is available on the Artremis website. The ETF market is in a state of flux, so some of these products might be discontinued and new ones could also be launched.

Some products allow you to trade individual currencies, whereas others offer exposure to a basket of currencies. Two exchange-traded funds offer exposure to the G–10 currency trade (DBV and ICI), and one (CEW) gives investors a basket of emerging market currencies.

Investors should note that double-leveraged and inverse ETFs involve special types of risks related to how often they rebalance exposures. Basically, unless markets move in a straight line, an inverse or short ETF can underperform a constant short position. And a double- or triple-levered ETF can also end up making you less (or losing you more) than just holding a steady double- or triple-exposed position.

Exchange-traded products can be easily bought and sold without seeking professional advice. But the fact that you need to sign in as a professional investor in order to obtain the presentations on some of these funds underlines the general recommendation to obtain professional advice.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to Inside Investing via Email or RSS.

Please note that the content of this site should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute.

Photo credit: tungstenblue

Hey there I am so happy I found your blog page, I really found you by mistake, while I was

searching on Digg for something else, Anyhow I am here now and would just like to

say cheers for a remarkable post and a all round enjoyable blog (I also

love the theme/design), I don’t have time to look over it all at the moment but I have saved it and also added in your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read much more, Please do keep up the superb job.

Interesting article. I am a currency trader and I would say the main practical difficulty in carry trading is that unless you work for a bank you are not likely get anywhere close to the true interest rate of either currency due to the spread on the overnight interest rates. You can see this if you look at websites like forexop.com, where they have done the fee calculations for a group of brokers. This was not a problem back when we had Australian dollar interest rates at 5%, but now with lower rates the spread becomes an issue and adds to the risk of the carry. btw I agree with you about the futures market, which is a better choice for the carry trader who has enough capital.