Berkshire’s Bottom Line More Relevant Than Ever Before, The Rest of The Story

Buffett’s sale of airline stocks validates FASB’S new accounting for equity securities

In a December 2018 piece, Berkshire’s Bottom Line More Relevant Than Ever Before, I refute the claims made in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece, I Can’t See Berkshire’s Bottom Line: A New Accounting Rule Makes It Difficult For Investors to Make Sense of Annual Reports, by Donald E. Graham — chair of the board of Graham Holdings Co. (formerly Washington Post Co. and previously an investee company of Berkshire Hathaway). In his opinion piece Graham echo’s Warren Buffett’s criticisms regarding a recently implemented accounting standard on the recognition and measurement of equity securities.

Recent Berkshire actions related to the sale of airline stocks shows Graham’s analysis was incorrect.

Graham argued that Berkshire Hathaway’s income statement is no longer relevant because of the requirement, beginning in 2018, that the change in the fair value of equity securities be reflected in net income rather than equity (i.e. other comprehensive). In very simple terms, Graham argued that reflecting the changes in equity security values – and the resulting volatility – made Berkshire’s income statement irrelevant because Berkshire holds these investments for the long-term and doesn’t intend to sell them.

In April 2020, however, Buffett sold Berkshire’s airline stocks. He told investors so at the Berkshire Annual Meeting in Omaha. By selling the stocks he transformed the unrealized losses in the March 31 income statement to realized losses – which we will see reflected in the June 30 income statement. In making the sale, Buffett refuted his earlier premise that the investments are held for the long-term and that the accounting, the bottom line, is not reflective of the economics.

During the Berkshire Annual meeting Buffett again notes, they are seeking to own companies – not the stocks – and they are doing it through the public purchase of shares, because rarely can you own 100% of good companies. In this clip of the meeting, Buffett spends about 15 minutes explaining that securities prices are not necessarily the long-term value, or prospects, of the business. He does this via analogy to the price your neighbor might quote you every day for your 160-acre farm. Indicating, it doesn’t change the long-term value. The moral of his story is that securities prices in the short-run do not reflect the long-term value of the business. The thing is that when it came to his investment in airline stock he took the securities price and got out – presumably because he thought the long-term prospects were worse than the securities price.

In my 2018 piece, I explain why Graham and Buffett’s thinking – as to why the reflection of changes in equity prices made the income statement irrelevant – was incorrect. Top among these reasons was that management’s intent (i.e. to hold the securities) does not change the value of the security and investors need to understand that value irrespective of management’s intent, because that intent can change – just as it did with Buffett and Berkshire’s airline holdings. As I noted at the time:

For equity securities for which there is less than a 20% ownership, or no significant influence, this new standard more prominently reflects the value of the securities using the price Berkshire would need to exit these positions (e.g. exit price fair value). Although Mr. Buffett considers these businesses rather than ticker symbols, as noted in his remarks, the accounting for such appreciation in net income better reflects the difference in these positions than those over which Berkshire has greater influence or control and can contribute to the business operations. It is more accurate to reflect the change in the value of these investments in net income as it occurs rather than simply when management’s intent changes and the decision to sell is made. Reflecting the realized gains in net income at that time inaccurately portrays such earnings as current period events, when in fact, the gains may have accumulated over many years. Now more than ever, the various methods of accounting for equity securities most accurately depicts Berkshire’s business model.

The method of ownership, publicly-traded securities, of stocks, is irrelevant to the analysis.

The accounting Buffett prefers – historical cost – is only available to him when share or security ownership exceeds 20% (i.e. the equity method or consolidation when ownership exceeds 50%). In the clip, he notes he thinks of such interests as “partnerships.”

Buffett states he owned approximately 10% interest in the four largest US airlines (American, Delta, Unitetd, and Southwest).

Whether Berkshire accounted for these on the equity method or fair value the resulting loss would have been based upon the traded value of the securities – investors just don’t get to see the change in value as transparently under equity method accounting or as prominently under the previous equity security accounting where such “volatility” in fair values was recognized in equity rather than net income.

Buffett’s intent changed in April 2020 when he sold the securities, but that didn’t change the value of the business or the value of the security.

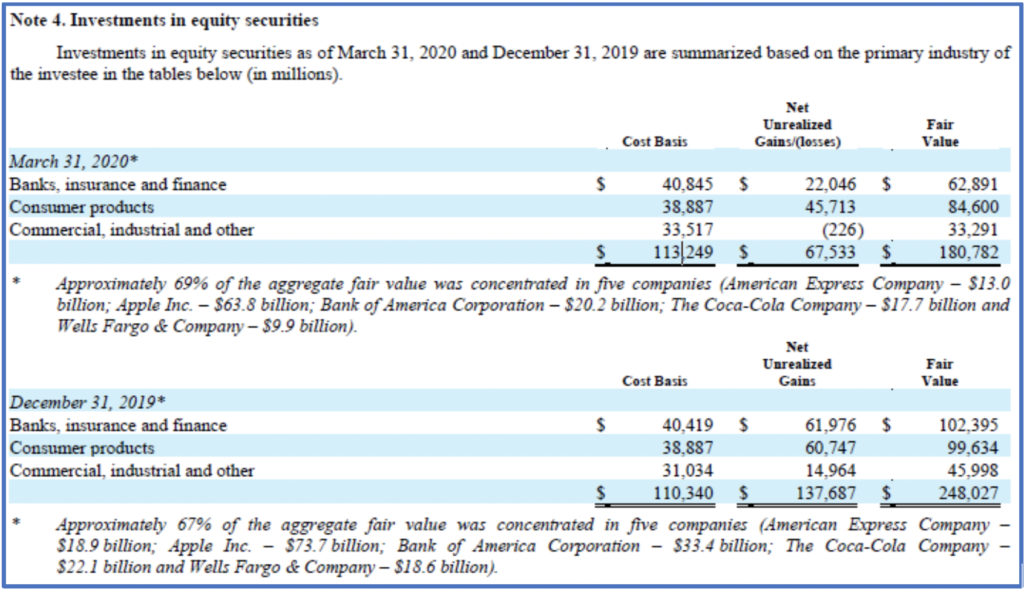

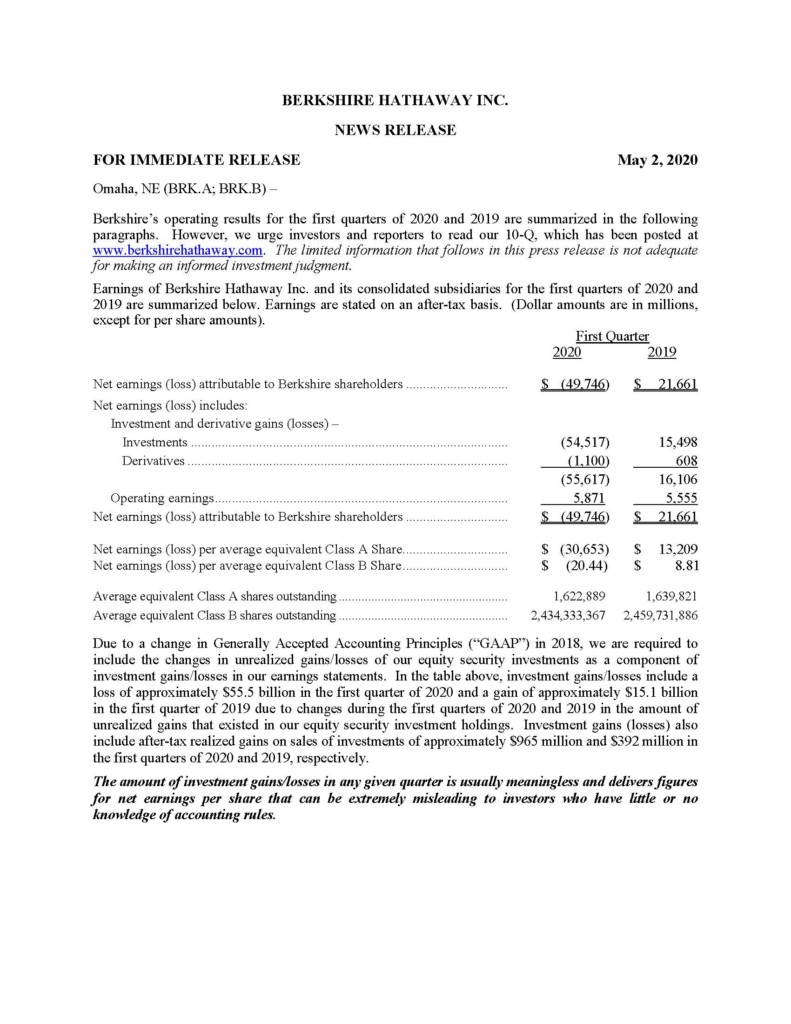

Despite significant time being spent on the discussion of airlines and how securities prices don’t reflect the value of the business, March 31, 2020, Form 10Q made no mention of any ownership in airlines. Neither the name of any of the airlines or the term airline are to be found in a search of the Form 10-Q. What is found in the following footnote on the cost, fair value, and net unrealized loss on the equity securities. Since December 31, 2019, the unrealized gain dropped $70.1 billion ($137.7 – $67.5 billion). When tax effected at 21% it amounts to the $55.4 billion or approximately the $54.5 billion loss on investments in the March 31, 2020 income statement. Presumably, airlines as classified with commercial, industrial, and others.

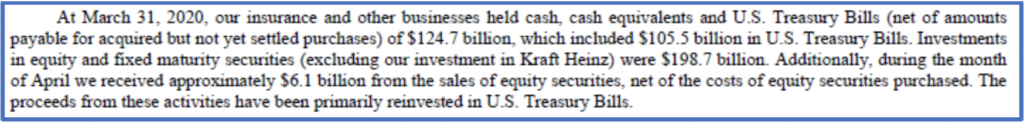

The only mention of a subsequent sale of securities appears on Page 16 of the MD&A where it is noted that in April Berkshire received $6.1 billion from the sale of equity securities. No mention is made of the realized gain or loss on such sales.

The 2019 Form 10-K also makes no mention of ownership of airlines. In Buffett’s 2019 annual letter he does, however, include the following table that highlights his ownership in Delta (11%), Southwest (9%), and United (8.7%). No mention is made of American.

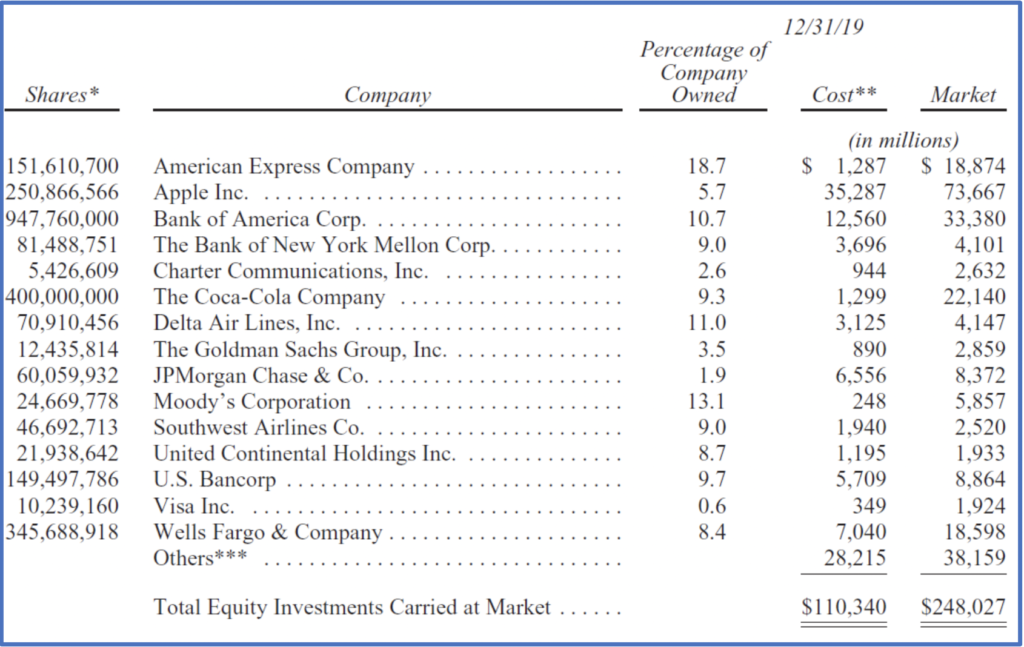

Out of interest using the cost and market value data from the table above we computed the market value of these December 31, 2019 ownerships at March 31, 2020, and during April 2020, using the stock prices on the lowest trading day for the airlines (April 27, 2020). We know from other reports that there were sales in early April but we do not know the exact ownership percentages or dates of disposal. These are simply approximations. From this, we can see that Berkshire went from $2.3 billion gain to a $1.9 billion loss and likely recognized a loss of somewhere between $1.9-$2.8 billion in April. A loss of 30-44% of the cost of the securities.

While the Berkshire Earnings Release says at the bottom that the investment gains and losses are “usually” meaningless, the $4.2 billion unrealized loss ($2.3 billion gain to $1.9 billion loss) was not meaningless. The tax effected unrealized loss of $3.2 billion represents 6.4% of Berkshire’s quarterly earnings.

Such losses became realized in the second quarter and demonstrate that the March 31, 2020 income statement accurately reflects the losses investors in Berkshire experienced. The accounting accurately reflected the value of these assets to the company – and its shareholders.

Investors just get to see it an incorporate it in their analysis more vividly than before.

The FASB has been strongly criticized for this change in accounting – one CFA Institute on behalf of investors strongly supported. As critics emerge in the future, the FASB needs simply to remind them of this case study to refute the claims.

Image Credit: © CSA Images