Why has the post-crisis recovery been so disappointing? Are we stuck in a world of diminished prospects and subdued demand?

Of course, to cure the world economy of its prolonged malaise, the causes must first be diagnosed, and for Turner, it comes down to one key factor: debt.

“Debt has become unsustainable across the world,” Turner explained, pointing to “the growth of debt in the advanced economies, not just over the few years before 2008, but over an entire half century.”

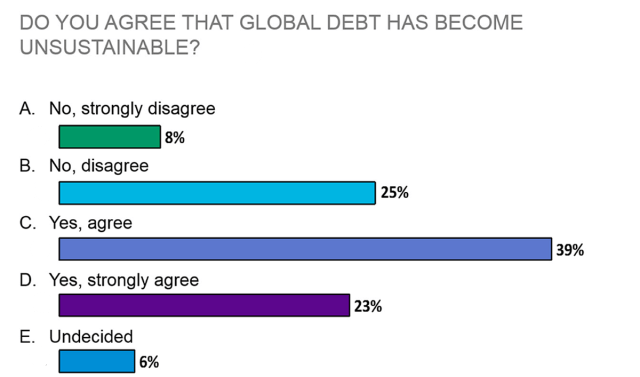

His assessment, that global debt has become unsustainable, was shared by roughly 62% of participants in an audience poll conducted prior to his session.

Turner has a unique vantage point from which to make such an judgment. As a key policy maker at the height of the financial crisis, he experienced the catastrophe firsthand. He was named chairman of the United Kingdom’s Financial Services Authority (FSA) in September 2008, just five days after Lehman Brothers collapsed. It was, Turner recalled, “rather like being appointed captain of the Titanic after you’ve hit the iceberg but before you’ve actually sunk.”

As he and other officials worked to stabilize the economy, Turner became convinced they were only skimming the surface of why 2008 had occurred — and why the recovery, both then and now, has been so weak.

That’s where Turner came to the debt situation. In 1950, he explained, household and corporate debt as a percent of GDP across all the advanced economies together, was roughly 50%. By 2008, that figure had ballooned to 170%, growing pretty much every year from 1950 to 2007 and accelerating in the early 1990s.

But it wasn’t that looming credit overhang alone that was the issue, it was what that debt was financing. It wasn’t going towards productive enterprises, like machinery, staff, or the components that generally drive economic growth.

“In the advanced economies, banks primarily lend money not for new investment but for the purchase of assets that already exist and in particular for the purchase of real estate assets that already exist,” Turner said. “The big picture here is that from about 1870 through to about 1950 or 1960, banks lent about a third of their money against real estate and the rest to non-real estate finance. But after about 1950, that relentlessly grew to reach 60% by 2007, and this actually understates the case because this is primarily residential real estate. There’s quite a lot of commercial real estate on top.”

“It matters because one of the features of real estate in advanced rich economies is that it is locationally specific,” said Turner. “Location matters enormously in real estate and it is difficult to create rapidly new attractive locations. Locationally specific real estate is an inelastic supply. And that has a very particular consequence, which is that if you lend money as a banking system against something which is an inelastic supply, the only thing that tends to give is the price.”

So more credit is extended against real estate. Prices go up. Borrowers and lenders believe prices will go up further and in turn borrow and lend more money.

“The cycle goes round and round and round until there is a crack of confidence,” said Turner, “and then it goes round and round in the other direction.”

These cycles of credit and real estate lending are not just part of the story of instability in advanced economies, according to Turner. They are the whole story.

“The trouble is,” Turner explained, “once we have these cycles of credit, asset prices, more credit, if we then get a swing from the exuberant upswing to the depressive downswing, if we get that when leverage is already high, we seem to enter an environment where the leverage never actually goes away. All it does is move around the economy.”

Debt is never paid down, in other words. It’s only shifted: from corporate debt to public sector debt, from advanced economies to emerging markets, and so on.

To support his case, Turner pointed to China.

“The growth of Chinese debt from something like 140% of GDP in 2007 to maybe 240% in 2016 — that isn’t just a coincidence,” he said. “That increase in Chinese debt was a direct consequence of deleveraging in the advanced economies.”

As US households tightened their belts to pay down their debts, China’s leaders feared reduced demand for Chinese exports and lower employment.

“And to offset that,” Turner said, “the Chinese authorities unleashed the biggest credit-fueled construction boom that the world has ever seen.”

In four years, China poured more concrete than the United States had used in the whole of the 20th century.

“So we live in a world in which, having created an enormous amount of debt, the debt doesn’t go away. It simply moves around within developed economies from the private to the public sector, and it moves around across the world.” said Turner.

Fiscal and monetary policy have all had a stimulative effect. But they create negative cycles of their own. As worries increase about the rise in public debt, austerity programs are implemented — just as the private sector is still deleveraging, creating more negative pressure on growth.

Ultra loose monetary policy leads to low or even negative interest rates. But that creates increasingly diminishing returns. “The transmission mechanism to the real economy isn’t very effective,” Turner explained, “because if companies and households are already over-leveraged, they’re not very sensitive to further cuts in interest rates.”

Currency mechanisms are no solution either, according to Turner. They may work for one country, but not all nations together.

“So we seem to be stuck,” said Turner. “All our classic policy levers to keep demand growing are blocked.”

The question becomes whether we are stuck in a low-growth, low-demand environment for the foreseeable future. Do governments and central banks have anything left in their arsenal?

“Governments and central banks together never run out of ammunition,” said Turner.

“You can use central bank money to finance tax cuts or expenditure increases in a fashion that does not require the government to borrow money,” he explained. “Or you can monetize existing government bonds. Central banks can buy existing government bonds and simply write them off, which frees up the government to run larger fiscal deficits in future.”

Turner acknowledged that the prescription may strike some as rather unorthodox. “When you say that, and if you’re a respectable member of society, people think you’ve gone a bit crazy.”

But Turner suggests that given the current economic stagnation, now is not the time for half measures.

Photo courtesy of George Raphel.

Chairman, Institute for New Economic Thinking

2016 Middle East Investment Conference

13 April 2016

Bahrain

Forecasts for global economic growth keep being revised downward with powerful deflationary forces depressing demand. In this engaging presentation, Adair Turner explores the root causes of this malaise, considering in particular the huge debt left behind by the 2008 financial crisis, the central role of China in recent developments, and the possibility that even more fundamental forces threaten to trap the world economy in a secular stagnation.

Gamal El-Din: Lord Adair Turner, chairman of the Institute for New Economic Thinking. He was chairman of the Financial Services Authority, where he rebuilt the institution’s reputation after the financial crisis and negotiated changes to the regulatory regime. Lord Turner was also chairman of the Overseas Development Institute and a visiting professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science and Cass Business School. He was chairman of the Pensions Commission, the Committee on Climate Change, and the Low Pay Commission and became a crossbench member of the House of Lords. He is the author of several books, including Between Debt and the Devil, 100 copies, by the way, of which will be available at a book signing during this evening’s reception. Please give him a very warm welcome.

[APPLAUSE]

Lord Adair Turner: Good afternoon, everybody. It’s a great pleasure to be here in Bahrain, and my job is to tell you why the correct answer to that question was D, strongly agree. Debt has become unsustainable across the world. And I have written a book about it, called Between Debt and the Devil. Now why did I write that book? As has just been said, I was formerly the chairman of the UK Financial Services Authority. And I actually became chairman of that on 20 September 2008.

Those of you who know your financial history will know that 20 September 2008 was five days after the collapse of Lehman Brothers. So I took over as chairman of the UK financial regulator as the entire global financial system was beginning to collapse, rather like being appointed captain of the Titanic after you’ve hit the iceberg but before you’ve actually sunk. We spent autumn 2008 — my life into autumn 2008 was dealing with the emergency. It was dealing with other regulators in other countries, with central bank governors, with ministers of finance. How do we stop this financial crisis turning into a complete disaster for the global economy?

By early 2009, we had achieved that basic stabilization. We were pretty confident that the crisis wasn’t going to go on and on. And we were then able to turn our attention to, what were the reforms needed to make the system stable for the future? And for four years, I was head of the policy committee of the international Financial Stability Board, which was the body charged by the G–20 political leaders with coming up with a plan to make sure we didn’t have such crises again.

And we therefore played a major role, along with the Basel Committee, in the design of the Basel III capital liquidity standards, the actions relating to shadow banking, the derivatives markets, etcetera. And I believe those measures have made the global financial system itself much safer than it was before. I think we are much less likely to get a suddenly developing financial crisis in which one bank fails and then we’re worried about another bank failing. But I also became convinced over those four years that we were really only skimming the surface of why 2008 had occurred. But even more importantly, why the recovery from 2008 across the world has been so disappointing, and so slow and so weak.

Because I think we have to remind ourselves that we live in a world of diminished expectations for the future. So if you were to look at a series of IMF medium-term growth forecasts, they keep on being downgraded and downgraded and downgraded. If you look in particular at forecasts for emerging market economy growth, look at what occurred in the different IMF forecasts of October 2011, then October 2012, then October 2013. They keep on being downgraded and downgraded.

And that is despite the fact that interest rates have been stuck at extraordinarily low levels, and stuck in ways that nobody anticipated. What this chart shows is a set of expectations of market interest rates for the UK Bank of England policy rate. And as you’ll see, at any one time, we always expect that they’re about to return to normality. And then they get downgraded and downgraded and downgraded. You may be beginning to recognize a pattern in these charts.

We live in a world of extraordinary low interest rates, historically low, both in nominal terms and in real terms. We have had seven years of policy interest rates at zero. If anybody had told you back in 2009, we’re going to have policy interest rates at zero, what do you think would happen? They would have said, oh my god, they must have gone mad. There will be hyperinflation. The economies will be roaring. The fact that we’ve got interest rate stuck at zero, and in some cases going negative, and the performance of the world economy as poor as it is, is extraordinary.

It’s also quite extraordinary how low inflation is and how difficult central banks across the world in the major advanced economies are finding it to get inflation back to target. The eurozone, the ECB, has a 2% inflation target. Well, it’s not doing very well at meeting that target, and in pursuit of it, has now put interest rates through to a negative level.

We live, as the IMF put it in January, in their then world economic outlook update, in a world of diminished prospects and subdued demand. And two days ago, when I was showing this chart in China, I said, “And I’m willing to bet you anything, that by two days later when I’m talking in Bahrain, the IMF will have further reduced its forecasts,” which indeed is exactly what they did yesterday. Before January, the forecast for world economic growth this year was 3.6%; then in January, it was 3.4%; now it is 3.2%. We live in a world of diminished prospects, subdued demand, as the IMF said yesterday. What is going on is increasingly disappointing, and we seem to face a risk of a synchronized slowdown.

My fundamental answer to the question, why has it been so disappointing, would be summed up on this chart. And this chart shows the growth of debt in the advanced economies, not just over the few years before 2008 but over an entire half-century. In 1950, private credit as a percent of GDP — so household and corporate combined across all the advanced economies together — was, as you can see on this chart, about 50%. And by 2008, it had grown to 170%. And as you can see, it grew pretty much every year from 1950 to 2007 and at an accelerating process after the early 1990s.

And that growth in debt was almost entirely explained, not by what our textbooks say that banks primarily do, which is lend money to productive enterprises for plant and machinery or other categories of investment, but that growth in leverage was almost entirely explained by a growth in real estate lending. What this chart shows is the product of a very fine analysis by three economists: Alan Taylor, Moritz Schularick, and Oscar Jorda. And what they’ve looked at is what the banking systems of advanced economies have been doing since 1870. It’s actually the banking system for most of the world, and for the US, it’s the banking system plus the capital markets, because the capital markets are so important, they’re the debt capital markets.

Now, I would ignore the oscillations in the early 20th century, when you have world wars and hyperinflation, and some pretty odd things happened to bank balance sheets. But the big picture here is that from about 1870 through to about 1950 or ‘60, banks lent about a third of their money against real estate and the rest to non–real estate finance. But after about 1950, that relentlessly grew to reach 60% by 2007. And this actually understates the case, because this is primarily residential real estate. There’s quite a lot of commercial real estate on top. And in the advanced economies, banks primarily lend money not for new investment but for the purchase of assets that already exist, and in particular for the purchase of real estate assets that already exist.

Now, why does that matter? It matters because one of the features of real estate in advanced rich economies is that it is locationally specific. It matters hugely whether that real estate is in the attractive part of town, whether it is in central London or out somewhere in some failing old industrial center. Location matters enormously in real estate, and it is difficult to create rapidly new attractive locations. Locationally specific real estate is an inelastic supply.

And that has a very particular consequence, which is that if you lend money as a banking system against something which is an inelastic supply, the only thing that tends to give is the price. And there are cycles that go on in advanced economies in which work as shown on this chart, whereby more credit is extended against real estate, the price of real estate goes up. That then generates in the minds of both borrowers and lenders the idea that prices are going to go up further, which makes them want to borrow and lend more money. And the cycle goes round and round and round, until there is a crack of confidence, and then it goes round and round in the other direction.

And it turns out that these cycles of credit in real estate lending, they’re not just part of the story of instability in advanced economies, they are again and again as work by the Bank for International Settlements, and in particular the chief economist there, Claudio Barrio, has shown — their work shows that these are again and again the whole of the story of financial instability in advanced economies. They’re what went wrong in Japan in the 1980s and ‘90s. They’re what went wrong in the Scandinavian banking crisis of the early 1990s. And they’re what went wrong in Spain, in Ireland, in the UK, and in the US again, in the run-up to 2008 and the post-crisis slow recovery.

And the trouble is that once we have these cycles of credit, asset prices, more credit — if we then get a swing from the exuberant upswing to the oppressive downswing, if we get that when the leverage is already high, we seem to enter an environment where the leverage never actually goes away. All it does is move around the economy. Now, what do I mean by that, that the debt never goes away, it simply moves around the economy?

Let me try and illustrate that by reference to Japan. Japan in the 1980s had one of the biggest of these credit and real estate booms that the world has ever seen. Over the course of about five years, credit extended by the banks to buy real estate went up about three times. The House of Real Estate in Central Osaka or central Tokyo went up about four times. In about 1990, early 1990s, there was a crack of confidence, and we swung from the green cycle to the red cycle, from the exuberant upswing to the downswing.

What then happened is that a group of companies — and in Japan’s case, it was primarily companies, not households — became convinced that they were over-leveraged, that they’d got too much debt. And they became determined to pay down their debt. And they became absolutely determined to pay down their debt, even when the Bank of Japan cut the interest rate to zero.

And that, which we can see on this chart — this is the Japanese corporates in 1990; PNFC stands for private non-financial corporates. In 1990, Japanese corporates were borrowing each year about 9% of GDP. They then became determined, however, to pay down their debt. They therefore cut their investment in an attempt to afford that, and they switched from being net borrowers from the financial system, as you can see here, to net savers, and they remain net savers for most of the next two decades.

The process of them cutting investment and becoming determined to deleverage drove the Japanese economy into a recession. In that recession, public finances deteriorated. Tax revenues went down. Public expenditures on unemployment benefit went up. And you can see the impact of that in the blue line, where the public sector moves from a surplus through to a deficit, where it has been stuck for the last 25 years.

And that deficit played a useful role. The stimulus of the public deficits helped offset the depressive effect of private deleveraging, but with the inevitable consequence that the debt didn’t go away. It simply moved around. And if you look in stock terms, in debt-to-GDP terms, this is the story of Japan over the last 25 years. The corporate sector has slowly deleveraged from about 140% of GDP to 100% of GDP, but the public sector has had its debt level go up from 60% to 240% of GDP. The debt hasn’t gone away. It’s simply moved from the private to the public sector, and the total level has increased and increased.

And it’s that pattern which has been repeated across the advanced economies since 2008. So that if you look on this chart, which is all the developed economies together, you can see in the run-up from 2004 to 2007, an increase from 150% to 170% debt-to-GDP of private debt, the final stage of that long-term chart I showed you earlier. After the crisis, there is some attempted deleveraging by the private sector, in particular by the US household sector. But that drives economies into recession in which public debt goes up by a much more than offsetting amount.

So that if you look at total debt in the developed economies, it’s the top blue line on this chart. And as you can see, total debt, private and public combined, as a percent of developed economy, GDP has not gone down at all. It has simply increased since the crisis and is still rising. Debt hasn’t gone away. It’s simply moved within the advanced economies from the private sector to the public sector.

And debt has also moved across the world. Because you can see here that the developed world growth in debt has at least slowed down, but we’ve had this dramatic growth in emerging market debt. And the most dramatic element of that growth in emerging market debt is the top line on this chart, which is China. And that growth of Chinese debt from something like 140% of GDP in 2007 to maybe 240% by 2016, that isn’t just a coincidence.

It isn’t just that there was a crisis in the advanced economies and then, quite separately, China decided to increase its debt. That increase in Chinese debt was a direct consequence of deleveraging in the advanced economies. Because the Chinese authorities in early 2009 were terrified, and they were rightly terrified, that deleveraging by over-leveraged US households was going to drive the US into recession and reduce demand for Chinese exports and produce a full unemployment in China.

And to offset that, and therefore as a deliberate direct consequence of that, the Chinese authorities unleashed the biggest credit-fueled construction boom that the world has ever seen. In the course of about four years, China poured more concrete than America did in the whole of the 20th century. And all of that extraordinary construction boom was credit financed. And what we are seeing across the emerging markets today is that faced with deleveraging in the advanced economies, which is depressing export demand, many emerging market economies have only been able to keep their growth going by having a significant increase in the level of private non-financial sector debt.

You can see it in here, in a series of Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, etcetera. So we live in a world in which having created an enormous amount of debt, the debt doesn’t go away. It simply moves around within developed economies from the private to the public sector. And it moves around across the world.

And that seems to leave us in a situation where all our classic policy levers to keep demand going are blocked. In the immediate aftermath of the crisis, everybody agreed that the good thing to do was just debt-financed fiscal deficits. At the G-20 meeting in London in April 2009, there was an agreement that all the major advanced economies should run large fiscal deficits to keep the global economy going. And they did that in 2009.

But the trouble is, after a while, and after that benefit has first been achieved — because its first immediate effect is undoubtedly stimulative — people start to worry about the rise in public debt. They worry about public debt sustainability. And then we get fiscal austerity programs, fiscal consolidation to try and control public debt. But then you enter an environment in which the public sector is trying to reduce its debt at the same time that the private sector is still deleveraging. And that will put the global economy into a deep recession unless we can offset it with ultra-loose monetary policy.

And so the conventional wisdom has been, let’s tighten fiscal policy but let’s have ultra-loose monetary policy. Short-term interest rates, zero or negative, long-term interest rates brought down by quantitative easing. And those have undoubtedly some stimulative effect. But the trouble is that after a while, that stimulative effect becomes less and less, and the transmission mechanism to the real economy isn’t very effective.

It isn’t very effective because if companies and households are already over-leveraged, they’re not very sensitive to further cuts in interest rates. The German bond 10-year yield is now — I think I looked this morning — 16 basis points. The cost of debt finance for a major German corporate is maybe 50 or 60 basis points. Suppose the ECB by more quantitative easing brings down 16 basis points to maybe 5 basis points, and the cost of funds to a big German corporate from 60 basis points to 50 basis points.

How likely is it that there are a group of German companies which, faced with that relatively small cut in interest rates, are going to go out and start investing? The answer is, it’s not very likely at all. Investment in the real economy is not all that elastic and sensitive to interest rate reductions, particularly when debt levels are already very high.

So people then say, “Oh no, that’s not how it works. It works because very low interest rates produce an increase in asset prices, and then people feel a bit richer and they start spending a bit more money.” That’s the transmission mechanism for QE. But it’s an indirect transmission mechanism, and one with a somewhat perverse effect of increasing inequality in a world where inequality is increasing in any case.

So finally people say, “Oh no, the transmission mechanism is through the currency. You have very low interest rates and your currency goes down, and you get a benefit on export demand.” But the problem with the currency mechanism is, although it can work for one country, if the rest of the world is in another position, it cannot work for all countries together. It has to be a zero-sum game at the level of the world economy.

If Japan attempts to stimulate its economy by driving down a lower value of the yen, that is a problem for China, for Korea, the eurozone. We cannot deal with the problem of a global debt overhang by devaluing our currencies against those of other planets. It just doesn’t work as a global solution. The net effect is that we appear to be in a situation where we are facing a debt overhang, and this is why your answer should have been D, a debt overhang so large that we seem to be faced with an avoidable and unattractive choice.

Either we are going to be stuck for many years with sustained low growth and low inflation with debt burdens that never decline, or we have to have large debt write-offs, and I think we have to have some debt write-offs, default, and restructuring. But it’s actually quite difficult to reduce global debt levels all that much by debt restructuring without that in itself depressing the economy. All we simply have to say, we’ll keep ultra-low interest rates for a very long time, and that will make all these debts sustainable.

But the trouble with that is, it undoubtedly makes existing debt sustainable, but it creates a very strong incentive for people to create new debts so we never get out of the debt overhang trap that we’re stuck in. So we seem to be stuck. And that is why, on the front page of the Economist two weeks ago, the headline was, “Out of Ammunition.” The statement was, there’s nothing more we can do, we’re stuck with low demand and low growth. And there is an increasing despondency across the world, reflected in the latest IMF figures, about whether we’ve got any levers that can get the global economy going around again.

So a crucial question is, are we truly out of ammunition? Is there nothing we can do to overcome this problem of subdued demand and diminished prospects? Well, I believe that faced with a deficiency of nominal demand across the world, governments and central banks together never run out of ammunition. Because although it is the case that your capacity to run debt-financed fiscal deficits might be blocked about by problems, concerns about public debt sustainability, and although it may be the case that ultra-loose monetary policy has a diminishing marginal effectiveness, that it doesn’t get through to the real economy, there is one thing that you can always do to stimulate an economy. And this is what Milton Friedman called “helicopter money,” but which I prefer to call overt money finance of increased fiscal expenditure.

What does that mean? It means that you can use central bank money to finance tax cuts or expenditure increases in a fashion that does not require the government to borrow money. Or you can monetize existing government bonds. Central banks can buy existing government bonds and simply write them off, which frees up the government to run larger fiscal deficits in future. And that is what my book says, in the final chapter, is one of the options that we should consider to get the global economy out of this deep post-crisis malaise.

But of course, when you say that — and if you’re a respectable member of society who wears a suit and tie — people look at you a bit askance. They think you’ve got a bit crazy, a bit sort of socialistic and left wing and inflation loving. But if this is socialistic and left wing and irresponsible and inflation loving, I am in quite good and rather remarkable company.

Because the person who most clearly said, in two articles in 1948 and in 1960, that faced with a deflationary problem we should use monetary finance to finance increased fiscal deficits, was that famous socialist, inflation-loving Milton Friedman, who in 1948 said that faced with these circumstances, the chief function of the monetary authorities should be the creation of money to meet government deficits. And that is of course precisely what Ben Bernanke said in 2003, when he said to the Japanese, you are stuck in such a deep deflationary trap, such a great difficulty of getting out of the problems created by too much private debt, that you should consider a tax cut for households and businesses that is explicitly coupled with incremental BOG purchases of government that, so that the tax cut is in effect financed by money creation.

And Ben has just repeated that in a blog, which you can see went up last week on Brookings Institute, where he said we should not exclude the possibility of permanent monetary finance of fiscal expenditures, in particular in Japan and the eurozone, because they may be the best alternative to get us out of this crisis. So I think, and so does Ben Bernanke and so would Milton Friedman, I think that we never run out of ammunition to deal with these problems of post-crisis malaise but that we may need to think about some very radical options.

Let me end, however, by saying not what should happen, but what do I think is going to happen in the major economies over the next 5 or 10 years. China has had this extraordinary credit-financed construction boom, and that is coming to an end, but not coming to an end. It’s producing enormous amounts of capital misallocation with apartment blocks being built in third- and fourth-tier cities, which will literally never be occupied. And with China facing a rapidly rising incremental capital output ratio, where it has to put more and more capital in to achieve a further increase in its GDP.

This is an enormous waste of resources. But the Chinese authorities are now struggling with the situation that you reach towards the end of a credit cycle, where you’re terrified about stopping it and you’re terrified about keeping it going. You’re terrified about stopping it because you’ll suddenly have a whole load of industries which are in extreme overcapacity, and you’ll end up revealing a whole load of bad debts. And you’re terrified of keeping it going, because then you’ll have an even bigger problem to deal with down the path.

And the story of China over the last year, two years, has been a set of oscillations, with them asserting that they’re going to end this credit boom, and then every time it seems to almost come to an end, they give it a further spurt. One of the things that’s happened in the last two months is that they’ve got terrified about the slowdown, and you’ll see in the latest figures coming out a sudden re-spurt of construction expenditure, all financed with credit, with credit as a percent of GDP going up and up and up.

Now over the medium term, I’m an optimist on the Chinese economy. I think they will achieve the shift to a service consumption–based economy. I think they’ll continue to grow at 5% or 6% per annum. But this is a very major slowdown in the infrastructure, construction, and industrial sectors. And this is what’s been driving the big fall in commodity prices across the world, and it’s not going to go away. It is going to continue to be a depressive effect on the global economy throughout the next several years.

What I do not think it is going to produce, however, is an international financial crisis at all like 2008. And that is because, although there is an enormous amount of debt within the Chinese economy, almost all of it is between different wings of the Chinese state. It is from local governments or state-owned enterprises to state-owned banks, rather than being owed to the rest of the global economy. And I therefore think the Chinese authorities have the capacity, the capability, to deal with the bad debts resulting, without that producing a global financial crisis. So for China, a very major slowdown is occurring, is going to continue in the industrial sectors, but not a major financial crisis.

Let’s get to the US. The US economy is doing OK, but only OK. The IMF forecast that came out today is 1.9% growth. Compared with what you used to think the US economy did after a crisis, the way that it bounced back — let’s take the early ‘80s, where there was the deflation produced by Paul Volcker driving out inflation, and then with three or four years where it grew at 5% per annum. 1.9% is not very good. It’s not sufficiently fast to drive up the employment rate as against a drive down the unemployment rate. And it’s not fast enough to drive up real wages, which for the bottom quarter of the American population haven’t increased for 30 years.

It’s not sufficient to put an end to the frustration with what’s happening in the American economy, which is driving things like both Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. The American economy has grown, has created jobs, but it is still in a position where GDP per capita in the US is about 10% or 15% below where it would have been on the pre-2008 trend. This is not a very good performance.

As for the UK, well, we’re doing what we always do in these circumstances. We say that we’re going to move towards manufacturing. We say that we’re going to move towards exports. And we’re not doing that at all. We’re growing at a reasonable pace. We’re creating a reasonable amount of jobs. But we’re doing it by borrowing lots and lots of money from the rest of the world, running a very large current account deficit, and getting going for another little property boom. It’s our classic way of dealing with problems. We are sort of happy with it. But it has the danger of an element of unsustainability.

But what I really want to focus on finally is Japan and the eurozone, the two economies which Ben Bernanke says should consider helicopter money. In Japan, there is going to be helicopter money. There is going to be overt money finance of an increased fiscal deficit. Because the thing you have to realize about Japan is that 25 years after it entered the post-crisis deleveraging problem, it is now in a situation where Japanese government debt will never be repaid in the normal sense of the word “repay.”

That’s not a statement of what should occur. That is a prediction; that is something on which I’m willing to take a bet. You are not going to see the Japanese government switch from having a primary fiscal deficit to a primary fiscal surplus and be able to pay down debt. And the second thing I am willing to bet you is that the JGBs bought by the BOJ will never, ever be sold back to the market. This is a permanent monetization exercise.

Now, it’s taken a bit of time for people to realize that this is occurring. Until recently, until 2014, the IMF would always produce a scenario for Japanese debt sustainability. And what they kept on saying is, what has to happen in Japan, so that it can get gross debt down to 200% debt-to-GDP and net debt after the holdings of the Social Security system down to 80% by 2030. And in 2010, it said, well, they’re now running a 6.5% deficit, and what they’ll have to do is turn that into a 6.4% surplus and to maintain that throughout the 2020s, and they’ll get this debt under control.

And then four years later they said, well, that sort of hasn’t happened — we’re still at a 6% deficit. But what we’re going to do now is achieve a switch from a 6% deficit to a 5.6% surplus in six years, and then we’ll maintain that throughout the 2020s, and then we’ll have debt sustainability. Well, what’s happened now is that they’ve stopped producing that scenario, because it’s beginning to look a little bit ridiculous. But what they do tell us is what they think might happen. The actual deficit in 2014 was 6.7%. Even in 2014, it was 5.4%. They think it may have come down to 3.2%, but it will still be a deficit in 2020.

What is going to happen in Japan during this year, I think, is that we are increasingly going to accept that this debt will never be repaid. It is going to be permanently monetized by the Bank of Japan. This will enable the Japanese government either not to go ahead with the sales tax increase, which is planned for April 2017, or to go ahead with that sales tax increase but to combine it with a huge fiscal stimulus which essentially returns all of that money immediately to Japanese citizens in what is called a voucher distribution. That is what I think is going to occur, and I think it is what should occur.

As for the eurozone, in terms of the dynamism of domestic demand, the eurozone for the last eight years has been even more disappointing than Japan. eurozone nominal GDP has grown even more slowly than Japan’s. But I do not think that in the eurozone we are going to see a monetary finance operation, a helicopter money operation. It’s not excluded. Mario Draghi, at his recent press conference, did not jump on it and say “We would never do it,” but it’s immensely difficult to do in the eurozone of one central bank and multiple countries.

Because whereas in Japan, with only central bank and one government, it’s pretty obvious when the central bank creates money that it’s going to the citizens of that country. In the eurozone, the moment you suggest a helicopter money operation, you get people saying, “But who’s going to get the benefit of this? Is this a transfer from German citizens to Spanish citizens, etcetera?” The political structure of the eurozone makes it incredibly difficult now to do what is required to stimulate demand.

And that reflects the fact that the eurozone is an incomplete monetary union without enough political unification, political integration to make it a stable monetary union. My forecast for the eurozone therefore is the following. The optimistic scenario is that the eurozone now will progress to the greater degree of centralization, the federalization, the creation of euro bonds, and to a coordinated fiscal stimulus required for it to be successful. I attach only a 10% probability of that.

At the other level, I would say there’s a 20% probability of significant breakup within the next five years. I think the most likely result is that we continue to muddle along with negative interest rates and QE for many years, that these are sufficient to prevent disaster and breakup, but they still leave the eurozone trapped with continued slow growth below target inflation and rising political pressures, which of course means that at some stage, this probability begins to shift through to this probability.

Overall, I think we are stuck in a very, very difficult position across the world. I think because of the debt overhang that we created, which is why the correct answer was D, we are stuck with problems that can only be dealt with by really quite radical actions. I’m pretty confident those actions will occur in Japan. I’m not confident that they will occur in the eurozone. I think we are stuck with severe problems created by too much debt creation. Thank you very much.

[APPLAUSE]

Gamal El-Din: Thank you, Lord Turner. Let’s talk through some of the themes that you went through. Lots of questions coming in from the audience. So I’m going to get straight to them. Two actually. On Brexit, A, will it happen, and B, what’s your preference? That’s an interesting one.

Lord Adair Turner: I have a strong preference for us staying in. That is not primarily on a narrow calculus of the economic event. Because I actually think when most economists look at it — and you can see it actually in the latest edition of the Economist, the summary of the economic models. Although most of them suggest a negative economic effect, it’s not a huge thing. I don’t personally believe that there’s some massive disbenefit or benefit from either in or out.

I’m basically an inner, a remainer, because I think that there is something about Europe which needs us as best possible to struggle to achieve unified views in the world. And I think that leaving the European Union at the moment would be a major political destabilization. The politics of Europe are in an incredibly fragile state because of the lack of success of the eurozone, because of the very large refugee and migration flows, and I think if Britain was now to leave, it would be a catalyst to yet more fragility in an already fragile continent.

So that’s why I am in favor; it’s a very emotional sense. It’s a commitment to Europe, rather than some calculus of the precise economic effect. As for what I think will happen, I think there’s about a 60% or maybe two-thirds chance that we will stay in, but I think there is at least a third chance that we will leave, go out. And I think that is a well more than the tail risk. That is a significant risk in the UK economy, the European economy, and indeed the global economy this year.

Gamal El-Din: The Fed doesn’t acknowledge a recession unless it’s over. Do you think that we are in a recession right now that will end in another Great Depression?

Lord Adair Turner: No, I don’t think we’re going to end up in another Great Depression like the 1929 to ‘33, because I actually think although our policies are imperfect, we do learn some things from history. Back in 1920 to ‘33, we decided that, faced with a banking crisis, you just had to let every bank go bankrupt. People rather like that at some stage. They say, that’ll teach people a lesson. Unfortunately, it teaches people a lesson, and it teaches a lot of people who have no responsibility for it a lesson as well.

Collapsing banks where one fails and another fails is a catastrophe. We know not to do that. That’s why we didn’t, 2008 didn’t turn into anything remotely like ‘29 to ‘33. So my worry is not a Great Depression. It isn’t even primarily some big new financial crisis, both because, as I said, I think China is not going to generate an international financial crisis. And I think the global financial system in itself is more stable than it was in 2008. My worry is simply, many years of disappointment, low growth, inadequate employment creation, therefore increasing political instability and pressures both in the developed markets and in many of the emerging markets. My worry is about the impact of sustained underperformance on our political and social peace, rather than a rapidly developing financial crisis, which I think is considerably less likely than it was before.

Gamal El-Din: Do you think the Fed will introduce QE4? It’s a contrarian view still, I would say. Or hike rates? Will this burst the bubble?

Lord Adair Turner: My best guess is that the US will be on a very gradual, and indeed glacial, path of raising — probably one, maybe two but not necessarily two increases this year. But if you ask me to guess where US rates will be in 2020, well, US rates won’t be higher than about 2 and 1/2%. UK rates won’t be higher than 1 and 1/2%. Japanese rates will be zero or negative. And ECB rates will be zero or negative. We are in a deep, lower-for-longer environment.

Could it be even more extreme from that? Well yes, you can imagine a case in which the US has a setback, and then you might be into QE 4. I think that’s a relatively low probability. I’m sort of — my base case proposal for the m, which is a case of an interest rate rising, and a reasonable but unexciting and somewhat disappointing rate of growth. That is not only my base case for the m; I had that with quite a high probability.

Gamal El-Din: So what’s the solution, then, for sovereign debt held by central banks? Is there a way out?

Lord Adair Turner: Yes. You’re going to see it in Japan. I mean, the Japanese government is issuing government debt at a pace of about 40 to 45 trillion yen per year. The Bank of Japan is buying JGBs at a rate of 80 trillion yen per year. The government of Japan owes debt equal to about 245% of GDP. Of that, about 100, 110% is actually owned by the social security fund. The IMF produces a figure for a net debt of about 140%, 150% of GDP. But of that 150% of GDP, 65% or 70% of GDP, so about half of that net, is already owned by the Bank of Japan. And at the pace they are buying and the government is issuing, there’s a date somewhere in about 2022, where there is no Japanese government debt owed to anybody other than entities which the government of Japan owns.

And if you only owe debt to things that you own, as anybody familiar with accounting consolidation knows, you don’t actually owe any money. So what is going to happen in Japan I think is that increasingly, investment banks and other commentators in the market are going to start publicizing the net debt figure after what is owned by the Bank of Japan, and we are going to realize that the Bank of Japan and the government of Japan could agree, a straightforward accounting exercise, in which the debt owed by the government of Japan to the Bank of Japan is replaced by a perpetual non-interest-bearing debt.

And perpetual non-interest-bearing debt is money. That’s what money is. Think about it. Money is a thing from your government or central bank that says that in return for it, they’ll give you another bit of money and it’s something which has no interest — money is perpetual, non-interest-bearing debt. The government of Japan will eventually… non-interest-bearing perpetual debt, which is money. We are looking at a monetized nation exercise, even though we have not yet explicitly recognized it as such.

Gamal El-Din: We’ll leave it there. Thank you very much, Lord Turner.

[APPLAUSE]

Silly me, and here I thought that helicopter money was a radical option.